My sister Mary and I standing on the east side of our sod-walled house probably in the mid 1940’s. Dad and Mom had re-plastered the outside giving it a mottled look. They had re-roofed the house adding dormers.

The above picture is of a sod-walled house formerly located southwest of St. Francis, Kansas, in Benkelman township. The house and farmstead were located on a rise about a mile or so south of the Republican River. I have heard the farm referred to as “The Downy Place.” A longtime friend of my late father thought that the house was constructed by the Downy family in about 1910.

The walls were constructed of Buffalo Grass sod. The wiry roots were quite evident when the sod was exposed. A conventional four-sided wood-shingled roof rested on top of the sod walls. The floor was of regular pine flooring, attached on floor joists resting on stringer supports above the ground. The walls were twenty-four to twenty-six inches thick. The inside of the sod walls were plastered with old-fashioned hog hair reinforced lime plaster, and then painted. The inside partition walls and ceiling were standard frame lumber covered with a fiber wallboard. Our family stretched poultry netting wire over the outside and pegged it down. A cement mix was then troweled over the outside. This is called stucco. Earlier plaster without wire reinforcement failed to stick for long periods.

The freezing and thawing action during the winter months would cause the cement stucco to crack and break. My mother was constantly patching the stucco and worrying about mice and the snakes that would follow. Her worries were justified. During a visit to the area several years ago, Merle Moberly, a family friend and neighbor from the past, told of being present during a noon meal when a young rattler peeked over at the junction of the ceiling and the top of an outer wall. He said that there wasn’t much fuss. My parents quickly dispatched it and carried it from the house and went on with the meal as if it was a normal occurrence.

I was not born in the sod house, but it is the first home that I can remember. However, my double cousin was born in this sod house. My next youngest sister Mary and I were born in a frame house on a nearby farm that my parents were renting at the time. We moved to the sod house farm when she was a baby and I was probably two and one-half years old. My youngest sister Joan was born near the time this picture was taken. She too, lived in this sod house as a baby. She was the first of us born in a hospital. I remember the emergency run and my mother telling my father he did not have much time to make it.

My sister Mary and I appear in this picture. I think the picture was taken about 1945 or 1946. It was taken during the winter. There are no leaves on the tree near the well and garden, and the cold frame used to start garden plants in the early spring is clearly in disuse. My sister wears lace-up shoes and warm thick stockings. I have on an ear-flap cap and overalls. I quit wearing overalls when I became a self-conscious teenager. In recent years, I’ve rediscovered the comfort and practicability of bib overalls.

At first glance the old sod house looks like something from a hardscrabble district. If it was, we did not know it. There were two other similar sod houses in the area that I know of. One was about a mile southeast of our farm. It was owned by the Owens family. It was in very good repair at the time. I don’t think it exists anymore. There were many sod houses in the county in the beginning. The early ones were very rough. It was a treeless country and lumber for construction just was not available. Kansas winters can be severely cold. A sod house is easy to heat in the winter and cool in the summer. We heated ours with coal and used corn cobs for fuel in the kitchen range. The hand-husked and gathered corn ears were ran through a mechanical sheller that stripped the grain from the cob and left the cob whole. I have eaten many a biscuit that was baked to perfection in the oven of a kitchen range using corn cobs for fuel.

A closer look tells us much about life in rural Western Kansas in 1945. To the far right, one end of a solar dryer, commonly called a clothes line, is visible. The chicken house was beyond that. The little house with a path was somewhere back there discretely hidden from easy view.

The ball bat with the taped handle leaning against the house indicated we were probably interrupted at play for the picture. The erosion around the base of the house was not from water but from the relentless currents of wind. The vines on the east facing windows kept the sun out and helped keep the house cool in summer. In winter they lost their leaves and let the warm sun in.

The bushel basket of fruit jars in the cold frame were being collected and stored for reuse. As many farm families did, we canned and preserved much of our table fare. The hoop with the slat cross was a screen used by my mother to sift the chaff out of wheat. She washed, then dried the wheat in the cook-stove oven. She ground the cleaned and dry wheat with a hand powered grinder to make flour for whole wheat bread and pancakes. We grew and produced most of our own food. The fertile soil grew a good garden when irrigated from the windmill.

One or two coal-oil lanterns always hung by the side door. The pail and string mops have significance. During a windstorm fine particles of sand and dust would come through the smallest of cracks. After a big blow there was always the chore of swabbing the place down.

The pipe protruding from the roof was a support for the radio antenna wire. The battery-powered radio was a source of news and entertainment. The resonant voice of Lowell Thomas reported the events of the war. “Fibber McGee and Molly” and “Amos and Andy” gave us mirth and laughter. “I Love a Mystery,” led us on thrilling adventures limited only by our own imaginations. On this radio I first heard Gene Autry’s “Back in the Saddle Again” and Eddy Arnold singing Tex Owen’s “The Cattle Call.”

With an old guitar I tried mightily to imitate Gene. My harried mother finally banished me to the outdoors. Taking refuge on the seat of the John Deere tractor, I plunked away for hours. I never succeeded in making a recognizable sound. After awhile the old guitar mysteriously disappeared.

Only the lower part of the small tower for the Delco wind-driven charger is visible in the picture. Anchored on top of the dormer, the wind-powered generator charged wet cell storage batteries located in the attic. They in turn furnished six volt, direct current electricity to the radio and to one lone light bulb on the ceiling of the kitchen. The batteries had to be serviced periodically. How do I remember the apparatus was six volt? Because, when the wind stopped and the storage batteries ran down, my father took the battery from the old Model A Ford and ran the radio from that battery.

The fact that the storage batteries in the attic had to be checked regularly led me into one of several close calls during an active childhood. My father went up the ladder and into the dormer to check the water level in the storage batteries. An adventuresome family cat followed him up the ladder and hid in the attic. My father left, closing the dormer door. A few hours later the cat put up a howl to be rescued. My mother told me to go open the dormer door and let the cat out. As I opened the door, a gust of wind caught the door and it knocked me off the roof. I fell headfirst onto the step below, breaking a board. When I regained consciousness, I was stretched out on a bed with my anxious parents hovering over me. They took me to Dr. Peck’s office in St. Francis, and after an examination he pronounced that he could find nothing wrong. However, I carried one shoulder down for several years, finally growing out of it.

It was about that time that my grandfather Cole started calling me “Toughie.” He was already calling my travel-prone older brother “Bigfoot.” Not long before the fall from the roof, a horse I was riding fell when an embankment caved off. I threw myself to the side, but the horse rolled on over me. The old high back saddle kept the horse’s weight off me (a few inches back or forward and I would not be here telling this story). The horse got up. I got up, pulled myself back into the saddle, and went about business as usual.

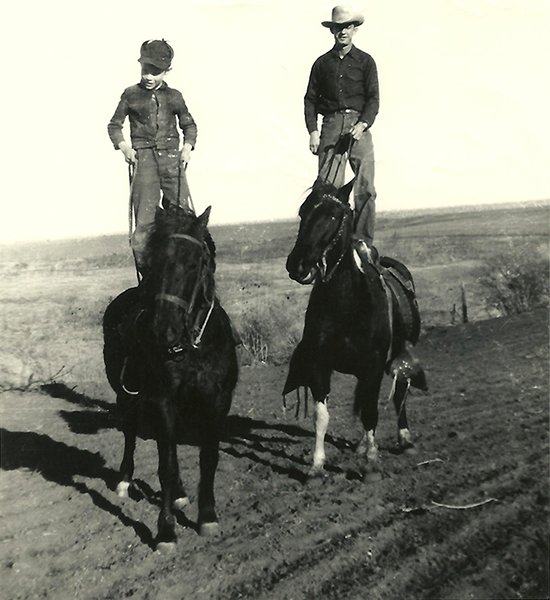

Getting on a horse was a chore for a kid. I could not reach the stirrup with my foot… My brother buckled a harness strap through the fork of the pommel and left it hanging so I could get ahold of it and pull up. Once up, I could not reach the stirrups from the top side either. My father finally bought me a youth saddle. Once I had that saddle, life was better.

My brother Wayne “Bigfoot,” was the cowboy among us. He was an irresponsible, happy-go-lucky teenager. Wayne started running away from home when he was fifteen. As he explained, “just to see what was on the other side of the hill.” Finally the folks just let him come and go as he wanted. He wanted to be a cowboy, and eventually he did work on several ranches in Nebraska, Colorado, and even in Florida.

The Cowboys

When my older brother Wayne returned home for a while, the first thing he would do was break any unbroken horses that dad had purchased while he was gone. In a few hours he had the big deep-chested gelding doing anything he asked it to do.

The stupid part-Shetland pony was a different story.

Not many days after this picture was taken, I was riding it along the road and a pheasant flew up out of the road ditch. The pony went crazy and dumped me in the gravel. I had a bad wrist spring as a result.

There was almost a ten year gap between Wayne and me. The folks had lost an eight-year-old girl ten days after I was born. She evidently died after a long illness from what we now call polio. My mother had her hands full with an inquisitive, overactive youngster and a runaway teen. She often said her worry was that I tried or would try to do every thing my older brother did. And I did, but I never ran away. I accepted responsibility early and stayed with it. Subsequently, my work has let me do many things and taken me to some amazing places. The adventure stories our Tennessee-born, Texas/New Mexico-homesteader grandfather told us no doubt influenced “Bigfoot” and “Toughie,” but in different ways.

A windmill in the corner of the barn lot pumped water to two large stock tanks. It was my job to switch the pipe from a full tank to the empty one. One full tank had to be held in reserve at all times. In my mind’s ear I still hear the kee-lunk, kee-lunk of the pumping wind mill. That sound is a heritage of the Plains born.

Rattlers were commonly found on the farm. When on foot I usually went protected by a couple of vigilant stock dogs. One dog was named Teddy, because he resembled a bear. Teddy was a dedicated snake killer. He would tease a rattler until it struck at him. The moment the rattler was stretched out from the strike, Teddy would grab it behind its head. After a few powerful shakes of Teddy’s head, blood would fly and the snake would start coming apart. I learned to always keep some distance. Teddy got bit once in a while, but developed an immunity. Perhaps, the snakes just did not get through his heavy black fur. Teddy had a litter-mate we called Timmy. He was an even-tempered dog, but he was not as smart as Teddy. Teddy was a natural heeler and made a good stock dog. Timmy ran at the cow’s head and never learned to round up or drive cattle very well.

Teddy the stock dog stands in front of the wood frame building being moved in near the sod house.

We named him Teddy because he looked like a bear. Don’t you agree?

Badgers were common on the farm. They were destructive and left dangerous holes for the horses to step in. One time Teddy and Timmy cornered a badger over in the rough land we used for pasture. He backed up against a soap weed (yucca plant) and proceeded to fight them off. Growing tired of the fight, he decided to dig himself in. Dirt and sand flew every direction. I watched in amazement as he dug while facing the dogs and holding them off. He was soon out of sight. Try as they might they could not dig him out. If you ever get a chance to look at a badger’s feet up close you will see they look like, well sort of look like miniature shovels with claws.

Many of my sod house memories are of the different horses we had. One mare was very gentle. She would ride me around until she grew tired of it, then she would lie down. I could kick and holler to no avail. When I gave up and stomped off toward the house, she would get up and go to the barn. Another mare learned that when I rode bareback, she could put her head down, give a slight buck, and slide me off over her head. It seemed to me that she always picked a patch of sand burrs to do it in. You haven’t experienced pain until you pull imbedded sand burrs out of your hide. I put a stop to that nonsense when I got tall enough and strong enough to push my saddle on her and jerk the cinch reasonably tight. We enjoyed many fun rides along the old irrigation ditch to the west of us. It was constructed by homesteaders in the 1890’s in a failed attempt to irrigate that dry land.

There was a large depression in a field to the southeast of the sod house. It was thought to be a former buffalo wallow. After the field had been worked or after a hard rain, my mother would take us arrowhead hunting. We often found arrowheads at the wallow site. A young boy didn’t have to stretch his imagination much to picture Roman Nose or Tall Bull hidden in the grass and weeds, bow and arrow in hand, waiting to ambush the varied types of game that frequented a buffalo wallow. We found large arrowheads and small “bird” sized arrowheads. That experience and visits to Beecher’s Island whetted my appetite for frontier history.

During the summer our parents would sometimes let Wayne and I sleep outside. Because of the rattler problem, we were relegated to making our pallets up on the floor of the hay wagon. We would go to sleep watching the twinkling stars. In our minds we were cowboys, camping out on a cattle drive. In my travels I’ve never found skies equal to Kansas skies, night or day.

In later years, I found that the cattle drovers trail called the Western Trail went through our area. Perhaps trail cowboys “Teddy Blue” and Tom Wray may have driven Texas cattle across those same buffalo grass and sagebrush hills. Wray Colorado was named for Tom Wray. He wintered a Texas herd there and became the first settler in the area.

My parents sold the sod house farm in 1947 and moved north into Nebraska. In 1950 we moved to Missouri. My brother Wayne was married by that time and stayed out west. Our mother died an untimely death from cancer in 1956.

Our father John Ryan with the sod-walled house in the background. He remembered the touring car as being a Starr brand. He did not own the property at the time but was visiting some one living there.

Dad told me he believed the picture was taken in the 1920’s.

I drove my father to Cheyenne County, Kansas for a visit in 1958. The old sod house was gone. The sod walls had been torn down and returned to the land they were plowed from fifty-some years before.

The old sod house homestead on the horizon viewed from the Highland school site. The sod house was gone by the time this picture was taken in 1958.

For more about Highland School, see the Oct. 24, 2012 post Alma’s Fire Shovel.

Another well-kept sod-walled house in the same community. It was the home of the Rollie Owens family. I remember visiting there as a child. Although it was in good repair, no one was living there when I took this picture in 1958.

When we lived there, my father had moved a frame house from a neighboring farm. That is the building on the house-mover’s trailer in the above picture with Teddy, our dog. My father had placed it near the sod house and used it for a bunkhouse and storage. That house had been added to and remodeled into a small home.

During a summer vacation in the mid-nineties I stopped in Cheyenne County, rented a plane and pilot, and flew over the farmstead on the way to Beecher’s Island. Sure enough, the outlines of the old buffalo wallow could be seen from the air. A Google map fly-over today shows a nice modern farmstead. A sprinkler crop irrigation system is used. I can still make out the outline of the old buffalo wallow.

Photo taken from the airplane flight over the sod house farm. As you can see here, it is now a modern, well-kept farm.

I was pleased that I could plainly see the outline of the old buffalo wallow where we picked up arrowheads. The outline is visible just below the airplane wing strut. The Republican River is in the tree line in the background.

The land of my birth still intrigues me. In fact, I could say my Sundown Trail started there.